(This article is inspired by a talk given at the Philosophy of Improvisation: Aesthetics of Imperfection Workshops)

Feldman’s compositions don’t impose themselves on you, and they refuse to shout about their meaning or importance – even their length. They also resist your attempts to predict what might happen next. His music is full of repetition, and yet nothing ever repeats. What I mean is that individual chords, textures and rhythmic ideas reoccur, but they are never (or very rarely) the same. – Tom service

Graphic musical scores ask you to withdraw meaning and information from symbols, pictures and texts. Many argue that such non-standard notation requires a performer to be visually literate and imaginative – the music depends on their individual choices of interpretation.

But where does the composer belong in this story? Do performers mistake the freedom associated with graphic scores for licence?

What are the pitfalls in interpreting graphic scores such as those by Morton Feldman? John Snijders, music lecturer at Durham University, made this the focus of his talk.

Cage, a contemporary composer, described Feldman’s music as “indeterminate with respect to its performance”.

If Feldman really was the originator of ‘chance’ music, then how can his indeterminate music be a recipe for catastrophe?

Feldman stated that “patterns are ‘complete’ in themselves and in no need of development – only of extension”. Perhaps then, according to his view, improvisation and interpretation is reliant on pre-existing forms.

But how do you really play a picture?

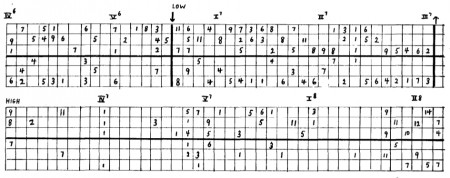

How do you know what the composer really wants if the sounds no longer have a determined symbolic shape, and if the instructions are indistinct. For example, Feldman rarely referred to ‘pitches’ – he much preferred ‘sounds’. This can be seen as vague.

How much ownership is a performer allowed?

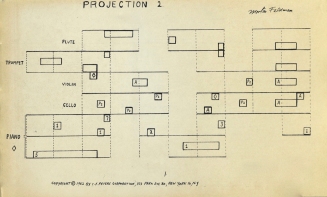

In Feldman’s Projections 2 very little is prescribed to the performer; for example, pitch is either signified as low, middle, or high. He is, however, very clear about instrumentation for the piece: flute, trumpet, violin, cello and piano.

Could Feldman’s scores be arbitrary in terms of notation but not sound?

Feldman felt so strongly about how he wanted graphic gestures to be interpreted and what he wrote Ixion in standard notation for performers who did not have the time or inclination to read his numbers.

Is the sound world in graphic scores the same as in notated scores?

Indeed, Feldman had a fixed ideas of sound. Should performers aim to meet these expectations of his, or use the score as a point of departure? Perhaps the score belongs to the composer but the performance of it to the performer. This would infer that the music does not solely belong to the composer.

“But you can always write your own piece”, concluded Snijders, in a humorous tone.